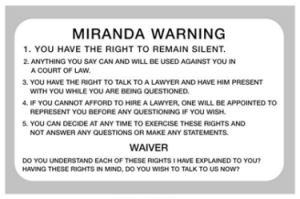

Countless times in the past I have written posts about clients who never would have been charged with a crime had they just kept their mouths shut and not spoken to the police. Many of these people though they could talk their way out of criminal charges. They were wrong. Others thought they did nothing and therefore had nothing to lose by talking to the cops. They were wrong. Some of these people listened to the cops who “suggested” they waive any constitutional rights and speak with them. They too were wrong. There are many instances where clients have told me that “the cops tricked me into talking to them”. This post discusses a recent Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court case where that tactic resulted in a partial reversal of a criminal conviction.

Articles Posted in Case Summaries

What Happens if You Give a Cop the Middle Finger in Massachusetts?

Just recently a former client called me with a new problem. He was driving on a residential street and saw a police officer he believed to be the same officer who arrested him several years ago. Even though he was acquitted of the crime, a drug distribution offense, he still harbored animosity towards the arresting officer. So, seeing this officer he did what most people wouldn’t have done. He gave him the middle finger. And guess what? He received a summons in the mail charging him with disorderly person. This incident prompted me to write about what happens if you give a cop the middle finger in Massachusetts.

Using Drug Sniffing Dogs: Commonwealth v. Feyenord, 445 Mass. 72 (2005)

More and more we are seeing searches and arrests made in Massachusetts that stem from the use of drug sniffing dogs. Take for the example the case of Johnny V. Nunez, a Boston man arrested last night for trafficking heroin. Nunez was stopped on Route 93 for routine motor vehicle violations. Drug paraphernalia was found in his car prompting the trooper to call for a K9 unit. The dog arrived, “hit” on the car and an ultimate search revealed the presence of more than a kilo of heroin. None of this would have occurred without the use of the drug sniffing dog. This post focuses on the legality of using drug-sniffing dogs in Massachusetts as discussed in Commonwealth v. Feyenord, 445 Mass. 72 (2005). Continue Reading

Defendant’s Right To A Public Trial Gets Unfavorable Ruling From Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court

Many Massachusetts attorneys that practice post-conviction litigation have been reviewing cases relative to the viability of raising the issue that a defendant was deprived of his Sixth Amendment right to s public trial—even during jury empanelment when spectators were excluded from the courtroom. Within the past few years it was discovered that many Superior Court Houses—particularly in Plymouth and Middlesex County—routinely prevented spectators from entering the courtroom during jury empanelment. The justification was often that the courtrooms were small and that there was simply not enough room to accommodate the venire and the spectators.  Continue Reading

Continue Reading

Massachusetts Search Warrant Exception Applies to Animals: Commonwealth v. Duncan, 467 Mass. 746 (2014)

On April 11, 2014 the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that the emergency aid exception to the search warrant requirement applies to animals. The case, Commonwealth v. Duncan was reported to the Court by a Superior Court judge after ruling in favor of the defense on a motion to suppress evidence seized during a warrantless search. This issue had never been addressed by the Massachusetts SJC. The facts and rulings are discussed below.  Continue Reading

Continue Reading

The Privilege Against Self-Incrimination After Testifying Under Oath: Commonwealth v. Martin, 423 Mass. 496 (1996)

There was once a time in Massachusetts when a witness who had already testified before a grand jury could simply invoke his privilege against self-incrimination and avoid having to testify in court. Then, in the mid 1990’s, when street gang violence was perhaps at its worst in Boston, things started to change. Prosecutors started to fight the trend of violent gang members who witnessed crimes refusing to testify. One way of doing this was to put the witness in the grand jury and lock him into his testimony. Many of these witnesses agreed to testify at this “closed” proceeding under the erroneous belief that they would never have to testify against the defendant in open court. I was often told that police officers and unscrupulous district attorneys would create this false sense of security. Then, when called to trial the witnesses would either feign memory loss or refuse to testify. This tactic was challenged in 1996 in the case of Commonwealth v. Martin, 423 Mass. 496 (1996).

Will Murder by Extreme Atrocity or Cruelty be Redefined in Massachusetts? The Concurring Opinion in the Case of Commonwealth v. Berry, 466 Mass. 763 (2014)

First degree murder in Massachusetts can be proved by the district attorney through one of three theories. One is by deliberate premeditation. To prevail under this theory the prosecution must show an intent to kill and that the decision to do so followed a period of reflection. The second way is through the felony murder rule. There, the prosecutor can secure a conviction by showing that the victim was killed during the commission of a felony that is punishable by a life prison sentence. The third way is with extreme atrocity or cruelty. Under this theory the jury must find that one of seven specific factors existed at the time of the killing.

How Massachusetts Handles Juvenile Life Without Parole After Miller v. Alabama, The Case of Commonwealth v. Brown, 466 Mass. 676 (2013)

In 2012 the United States Supreme Court decided the case of Miller v. Alabama, 132 S.Ct. 2455 (2012). There, two fourteen year olds were convicted of murder and sentenced to life without parole, a mandatory sentence under their state law sentencing schemes. The Supreme Court held that sentencing laws that mandate life without the possibility of parole for juvenile offenders violates the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution. This is so because such laws do not permit the judge from considering age, maturity, family environment, appreciation for their actions and other circumstances attendant to their youth and the crime they committed. Exactly what that would mean to juveniles serving sentences of life without parole in Massachusetts was not made clear until Christmas Eve 2013 when the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court rendered its opinion in Commonwealth v. Brown, 466 Mass. 676 (2013).

How to Summons or Subpoena Evidence for a Criminal Case in Massachusetts, Rule 17 and Commonwealth v. Lampron, 441 Mass. 265 (2004)

This process used to be so easy. Simply draft a subpoena identifying the materials you wanted and have it served on the keeper of the records for the entity in possession of the materials. Some lawyers had summons direct delivery to their law office. Others had it delivered to the clerk’s office where the case was pending. Sometimes the criminal defense lawyer would get a call from one of the assistant clerks telling him that the documents were delivered and available for photocopying. Some clerks might tell the lawyer that the material was too voluminous for the clerk’s office to keep so the lawyer was instructed by the clerk to keep it himself. If the material was not delivered the defense lawyer would ask for the judge to order compliance with the subpoena. The keeper of the records would then have to produce the material or appear, usually with counsel, and state why the records could not be produced.

Commonwealth v. Gonsalves, A Massachusetts Offshoot Of The Crawford Rule

In many Massachusetts criminal cases, particularly domestic violence cases, a witness asserts a privilege not to testify at a trial. The most common privileges that are asserted are the marital privilege and the privilege against self-incrimination. Simply stated, in most circumstances the government cannot force a spouse to testify against his or her spouse–this is referred to as the marital privilege. Also, a witness cannot be forced to testify if some of the testimony will incriminate him or her.

If the Commonwealth plans to go to trial and cannot call this witness it may try to call a witness that heard the person make the statement that incriminates the client. In this situation the trial attorney must file a motion to exclude the statement of the witness who is reiterating what a non-testifying witness stated. This is generally done as a “Motion In Limine” filed prior to trial. Depending on the court, this can be done on a date prior to the trial date or immediately before trial. One of the seminole cases in this area is Commonwealth v. Gonsalves, 445 Mass. 1 (2005).

Massachusetts Criminal Defense Attorney Blog

Massachusetts Criminal Defense Attorney Blog